Dec. 2020 Science Corner | “Integrating art and science to communicate the social and ecological complexities of wildfire and climate change in Arizona, USA”

The authors followed an art exhibit, Fires of Change, from conception through public exhibition to understand how both participants and viewers of the art exhibits were able to interact and learn about fire and climate science through 11 individual artists’ interpretations.

Authors: Melanie Colavito, Barbara Satink Wolfson, Andrea E. Thode, Collin Haffey & Carolyn Kimball

Interview and story by: Phil Saksa & Jessica Alvarez

This month, we’re focusing on something unique: science communication through art! Here at Blue Forest, we think a lot about how to communicate effectively to a wide variety of audiences: scientists, utilities, investors, stakeholders, foundations and government agencies to name just a few. So when we came across this amazing study highlighting an innovative approach of using art to describe fire regimes in the southwest U.S., we felt compelled to share it with all of you.

The authors followed an art exhibit, Fires of Change, from conception through public exhibition to understand how both participants and viewers of the art exhibits were able to interact and learn about fire and climate science through 11 individual artists’ interpretations. We had the opportunity to talk with the authors on how the project was envisioned and their findings from the study.

“The impetus for this exhibit really came out of a similar project developed initially by the Alaska Consortium, for which this iteration was really able to build upon through the Southwest Fire Science Consortium,” explained Barbara Satink Wolfson, Program Coordinator for the Southwest Fire Science Consortium at Northern Arizona University (NAU).

After the Alaska project, the Joint Fire Science Program office announced funding for similar projects which facilitated the development of Fires of Change.

What made this project both different and unique, was not only the location of the research, but also the longer length of the field workshop, the length of time the artists had to produce the artwork, the different perspectives from the researchers involved and the amount of funding available where they were actually able to fund the artists for their time and participation.

“There is a lot of social science that documents getting different groups of people together in person, whether scientists and land managers or scientists and artists, is a great way to develop a shared understanding and shared outcomes through a collaborative and iterative learning process, that both represent the science but can also communicate it in another way,” explained lead author Dr. Melanie Colavito, Director of Policy and Communications with the Ecological Restoration Institute at NAU.

Two of the key differences, according to the researchers, were the significant social science behind the project and having a good curator onboard who not only was good at understanding art but had also done various projects with other scientists at NAU.

“Having a curator as the artists’ point of contact that could serve as the translation role between art and science helped facilitate the creation of a better product than some of the earlier efforts in this space,” said Collin Haffey, Conservation Manager with The Nature Conservancy in New Mexico.

Conversely, in discussing what the researchers themselves gained from the experience, the consensus was that they all had an opportunity to learn about and experience art firsthand. Allowing the researchers to become students and work with artists for the first time was a huge part of the project’s success, according to Dr. Andrea Thode, Professor of Fire Ecology & Management at NAU.

“Going into the field and having those in-person experiences, personal relationships built, and being able to have those conversations was really, really critical to the success of this project,” she said.

“Having dinner over a campfire and those types of shared experiences away from screens and technology helped develop those relationships,” added Carolyn Kimball who is the Former Senior Program Coordinator of LCI at NAU.

For Haffey, the broader lesson learned was the importance of seeking out new ways of communicating, seeking out new constituencies to tie your message to, and thinking creatively about new ways to engage with other non-science communities.

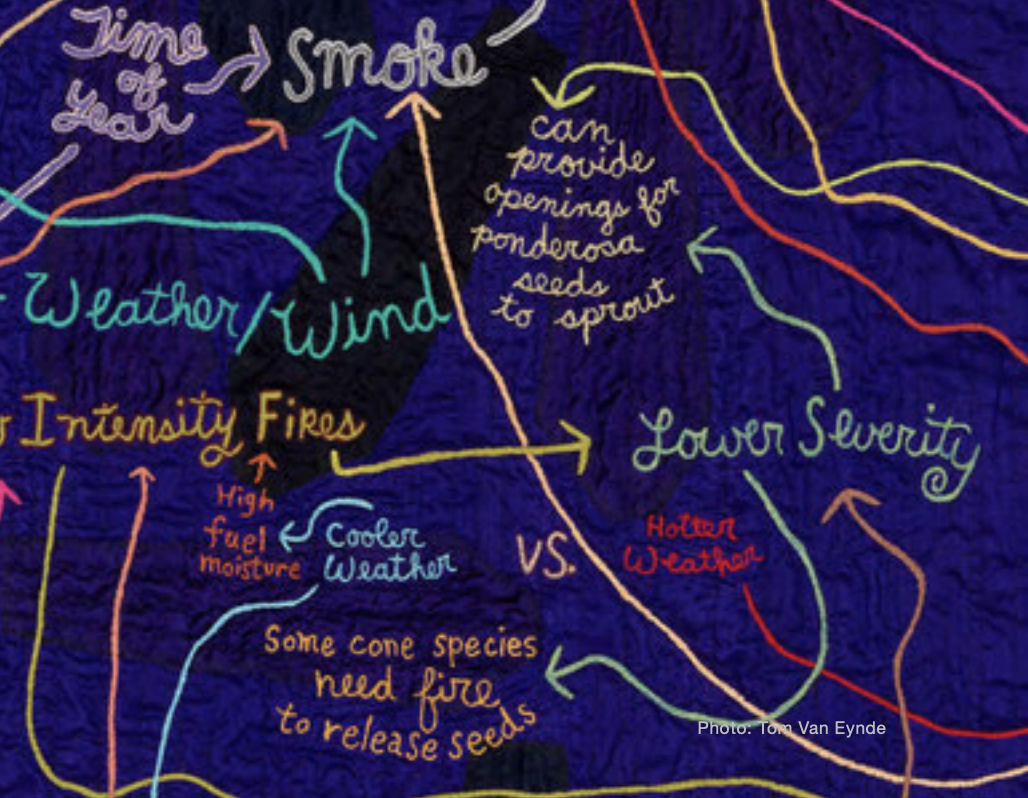

Drawing 12,000 visitors to the exhibition was in large part facilitated through the diversity of interested audiences and the arts organizations that have a strong outreach network. People will sometimes shy away from things labeled science as opposed to art which opens up the experience to a lot more people who might not otherwise feel that the work is approachable. “The integration of scientific quotes in the exhibit space with the artworks resulted in a nice integration of science without being overwhelming,” explained Dr. Colavito.

As an indication of the success of this unique collaboration, “one of the artists did a show in Fresno on fire following this exhibition and has kept going on that line of thought, translating science into art,” said Satink Wolfson.

“Working with the Festival of Science in Flagstaff was really helpful in bringing some elementary and middle school students into the exhibit, but there could be even greater opportunities to be integrating this experience with schools and classrooms,” added Dr. Thode.